How to Write a Winning Grant Proposal

A winning grant proposal is a persuasive business case wrapped in compliance. Funders don’t just want inspiring ideas; they want proof your organization can deliver measurable outcomes, manage risk, and follow required rules. That’s why the best grant proposal writers think like a program director, a finance lead, and a reviewer at the same time.

From an expert practitioner’s perspective, the most common reason a grant proposal loses isn’t the mission—it’s misalignment. The project doesn’t clearly match the funder’s goals, the outcomes aren’t measurable, the budget doesn’t connect to the work plan, or the application misses mandatory requirements.

Some funders will reject late or incomplete submissions without review, so execution matters as much as storytelling. For example, arts grants explicitly warn applicants not to wait until the last minute to submit the SF-424 and note that late, ineligible, or incomplete applications won’t be reviewed.

Another reason proposals fail is governance and compliance gaps. If you’re applying for federal funding, registrations and identifiers can be gating items. Federal assistance often requires a Unique Entity Identifier (UEI) and/or registration in SAM.gov, with exceptions limited and controlled by regulation.

And once awarded, many recipients must follow government-wide administrative and cost principles under 2 CFR Part 200 (Uniform Guidance), which saw substantial updates effective October 1, 2024.

This guide walks you step-by-step through writing a grant proposal that is easy to score, hard to reject, and ready to manage after award—using real-world examples, reviewer logic, and up-to-date compliance references.

Understand What “Winning” Means to Reviewers

A “winning” grant proposal is the one that makes the reviewer’s job effortless. Reviewers typically score using a rubric: alignment, need, approach, evaluation, capacity, and budget realism. Your goal is to remove doubt in every category.

Start by thinking like a reviewer reading 20–60 applications. They’re looking for fast clarity: Who are you? What problem are you solving? Who benefits? What will you do, when, and with what resources? How will you measure success? Where are the risks, and how will you manage them? A strong grant proposal answers those questions in the first 1–2 pages, then proves each claim with specifics.

A practical scoring mindset: every paragraph in a grant proposal should either (1) increase confidence you can deliver outcomes, (2) reduce perceived risk, or (3) demonstrate fit with the funder’s priorities. If a paragraph doesn’t do one of those, delete it.

Real-world example: A community health nonprofit wants funding to expand mobile screening. A weak grant proposal says, “We will increase access to care.”

A winning grant proposal says, “We will deliver 1,200 screenings in 12 months across five high-need zip codes, reduce missed appointments by 20% using SMS reminders, and report monthly outcomes through a secure dashboard, with clinical oversight by a licensed medical director.” Same mission—different confidence.

Finally, remember that many funders are compliance-driven. If you’re using government forms like SF-424, follow the applicable application guide and instructions precisely. A technically perfect submission can be the difference between funded and rejected.

Choose the Right Funding Opportunity and Prove Eligibility

Before you write a single line of your grant proposal, confirm the opportunity is a true match. “Right fit” is about mission and mechanics: eligibility, geography, award size, match requirements, and allowable costs.

Eligibility is where many applications die quietly. For federal awards, funders may require a UEI and entity registration in SAM.gov for prime applicants, and SAM.gov explains that registration supports applying for federal assistance and includes assignment of a UEI.

Regulations in 2 CFR Part 25 also cover UEI/SAM requirements and exceptions, which exist but are limited and agency-controlled. If your registration is expired or mismatched (legal name, address, banking info), you can lose weeks and miss deadlines.

Beyond registrations, check:

- Applicant type: nonprofit, local government, school district, small business, institution of higher education, tribal government, etc.

- Cost share/match: cash vs in-kind, documentation expectations.

- Award period and start date: can you realistically hire, procure, and launch?

- Reporting obligations: performance reports, financial reports, audit requirements.

Real-world example: A workforce nonprofit applies for a technology grant to build a training lab. The NOFO prioritizes rural counties and requires employer commitments. Their first draft grant proposal focuses on youth unemployment broadly.

The revised winning grant proposal maps outcomes to the NOFO priorities, adds letters from three employers guaranteeing interviews, and budgets equipment under allowable cost categories with a procurement plan.

When in doubt, write a one-page “fit memo” before the grant proposal. If you can’t clearly connect your project to the funder’s stated goals using the funder’s own language, you’re forcing it—and reviewers will feel that.

Build a Proposal Strategy Before You Start Writing

Winning grant proposal work starts in planning: a clear theory of change, a realistic project plan, and evidence that your team can execute. Strategy prevents the most damaging proposal problem—internal contradictions.

Begin with a logic model:

- Inputs (staff, partners, tools)

- Activities (what you will do)

- Outputs (what you will deliver)

- Outcomes (what will change)

- Impact (long-term community benefit)

Then build a work plan that lists tasks, owners, timing, dependencies, and deliverables. This becomes the backbone of your grant proposal narrative and your budget justification.

Next, define your reviewer proof:

- Need evidence: local data, waitlists, service gaps, baseline metrics

- Capacity evidence: past performance, staffing, systems, governance

- Feasibility evidence: partner MOUs, procurement readiness, site access, permits

- Evaluation evidence: instruments, data plan, targets, reporting cadence

If you’re applying for federal funds, design your program with post-award compliance in mind. 2 CFR Part 200 (Uniform Guidance) governs many administrative and cost rules and was substantially updated with changes effective October 1, 2024.

A strategic grant proposal anticipates documentation requirements: time and effort, procurement standards, subrecipient monitoring, and internal controls.

Future-facing edge: more funders are moving toward standardized data collection and common forms. For instance, NIH has policy notices about implementing “Common Forms” for biosketch and current/pending support with due dates on or after January 25, 2026.

Even outside research funding, this trend signals a future where funders compare applicants more directly—meaning your grant proposal should be both narrative-strong and data-structured.

Write a Compelling Executive Summary That Sells the Whole Grant Proposal

The executive summary is the highest ROI section of any grant proposal. Many reviewers form an initial score range from it alone, then read the rest to confirm or adjust. Your summary must stand alone as a complete, scannable business case.

A strong executive summary answers:

- Who you are: mission, credibility, and track record in one sentence.

- The need: a specific community problem with evidence.

- The solution: what you will do, for whom, where, and how.

- The outcomes: measurable targets and timeline.

- The ask: amount requested and what it buys.

- Why you: unique advantage, partners, and readiness.

Use funder language without sounding robotic. If the NOFO emphasizes “evidence-based interventions,” include the intervention model and cite evidence briefly. If the funder emphasizes “equity” or “rural access,” make that explicit in your outcomes and staffing plan.

Real-world example executive summary framing (conceptual):

“Over 18 months, we will expand our small-business technical assistance program to serve 300 first-time entrepreneurs, deliver 1,800 hours of coaching, and increase participant revenue by an average of 12% within 6 months of program completion. Funds support two advisors, a data analyst, and a client management system.”

That’s a winning grant proposal summary because it’s measurable, resourced, and time-bound.

Also include submission readiness cues. For opportunities using government portals, emphasize that you will submit early and follow required forms. Agencies explicitly warn about last-minute SF-424 submissions leading to preventable failures.

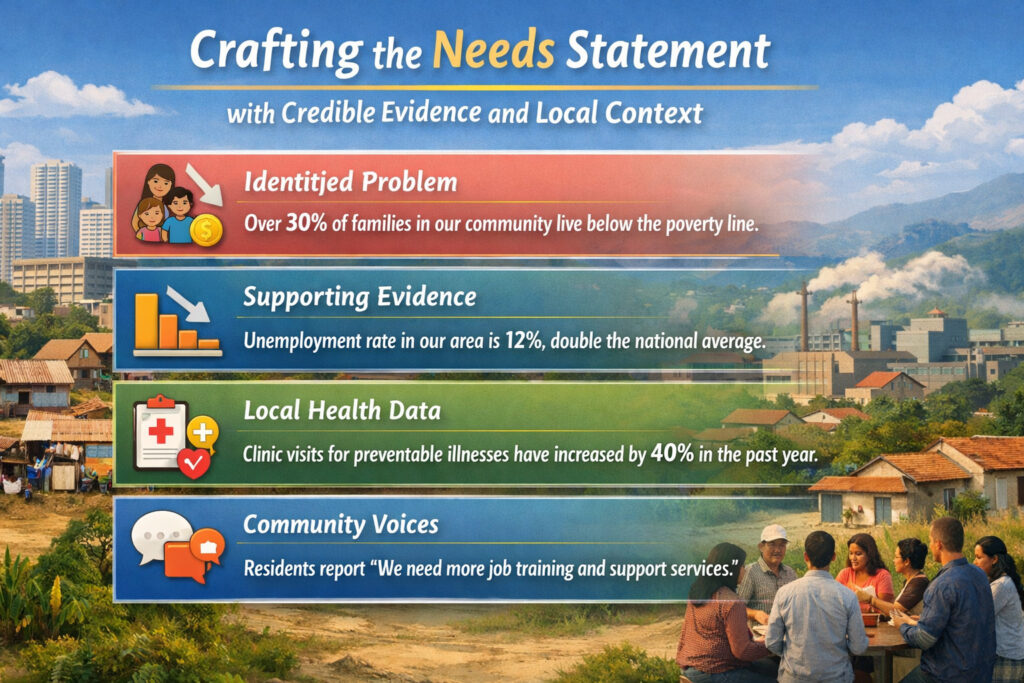

Craft the Needs Statement With Credible Evidence and Local Context

The needs statement is not a sympathy story; it’s a problem definition with proof. A winning grant proposal needs a statement that uses credible data, shows why the issue matters now, and establishes urgency without exaggeration.

Use a layered approach:

- Macro context: national or statewide trends (brief).

- Local impact: county/city/zip code metrics and disparities.

- Service gap: what’s missing today (capacity, access, affordability).

- Why current solutions aren’t enough: constraints and barriers.

- Target population definition: who you will serve and why.

Strong evidence sources include state agencies, local health departments, school district reports, labor market data, and peer-reviewed studies (when relevant). Avoid cherry-picking. If data is imperfect, acknowledge it and explain how your program will improve measurement.

Industry terminology that helps reviewers trust you:

- Baseline, target, KPI, output vs outcome

- Service utilization, referral pipeline, retention, dosage

- Risk factors, protective factors, intervention fidelity

- Cost per client served, unit economics (for scalable programs)

Real-world example: A housing nonprofit proposes eviction prevention. Instead of generic claims, the grant proposal should quantify: eviction filing rates by neighborhood, average rental arrears, legal aid capacity constraints, and the projected impact of mediation and emergency assistance.

Add a “so what” bridge: connect the need directly to the funder’s mission. Reviewers score based on alignment, so explicitly state how solving this problem advances the funder’s priorities.

Finally, avoid common credibility killers:

- Overstating need without citations

- Using outdated statistics without context

- Confusing outputs (workshops delivered) with outcomes (behavior change)

A winning grant proposal makes the need undeniable and the solution logical.

Design the Project Narrative Reviewers Can Score Easily

The project narrative is the core of your grant proposal. It must be specific enough to implement tomorrow and clean enough to score today. The best structure is “promise → plan → proof.”

Define goals, objectives, and SMART outcomes

Goals are broad. Objectives are measurable. Outcomes must be SMART:

- Specific

- Measurable

- Achievable

- Relevant

- Time-bound

For example:

- Weak: “Improve literacy.”

- Strong: “Increase reading proficiency by one level for 70% of 3rd-grade participants within 9 months.”

This clarity helps reviewers see feasibility and helps your team manage the grant after award.

Explain methods and implementation details

Describe:

- Program model (evidence-based approach if applicable)

- Participant recruitment and eligibility

- Staffing roles and supervision

- Service delivery flow (intake → services → follow-up)

- Partnerships and referrals

- Quality assurance (fidelity checks, training)

Real-world example: A small business accelerator’s grant proposal improves significantly when it includes a weekly delivery schedule, mentor qualifications, curriculum outline, and participant milestones.

Include risk management and contingencies

Winning grant proposal writers name risks before reviewers do:

- Hiring delays → maintain contractor bench

- Partner drop-off → secondary referral partners

- Data privacy → policies, access controls, retention limits

- Supply chain → alternate vendors, procurement lead time

This matters more for public funding. Many recipients must operate under Uniform Guidance rules (2 CFR Part 200), which were updated effective October 1, 2024—so show that your internal controls, procurement planning, and documentation practices are mature.

Build a Budget and Budget Narrative That Can Survive Scrutiny

The budget is where many promising grant proposal narratives collapse. Reviewers want a budget that is reasonable, allowable, and tightly connected to the scope of work.

Start with the work plan and build the budget from tasks:

- Personnel tied to specific deliverables

- Fringe calculated consistently

- Travel justified by implementation needs

- Equipment and supplies aligned to program delivery

- Contractual/subawards supported with partner scope

- Indirect costs per applicable rules or negotiated rate

If you’re applying for government funding, you must understand cost allowability and documentation expectations. Many federal awards follow 2 CFR Part 200 cost principles and administrative rules, and those rules were substantially updated with an effective date of October 1, 2024.

That should influence how you describe procurement, subrecipient monitoring, and internal controls in your grant proposal.

Write a budget narrative (budget justification) that:

- Explains calculations (salary × % effort × months)

- Links each line item to activities

- Avoids “miscellaneous”

- Notes procurement method for major purchases

- Clarifies subrecipient vs contractor roles

Real-world example: A youth program requests $120,000 for staff. Reviewers question it until the budget narrative ties two case managers to 120 youth, 15 clients each per month, with retention and follow-up built into job duties. The grant proposal becomes “cost per outcome,” not “money for staff.”

Also plan for compliance-driven reporting: performance reporting, financial reporting, and audits. Even if the funder is private, they often mirror public-sector expectations.

Master Submission Mechanics: Registrations, Forms, and Compliance Traps

A technically perfect grant proposal can still fail if you miss submission mechanics. Treat compliance as a project with deadlines, owners, and backups.

For federal applications, entity registration is often required. SAM.gov explains that organizations seeking federal awards need registration to apply for federal assistance, and the process includes assignment of a UEI.

Regulations in 2 CFR Part 25 describe UEI and SAM requirements and include narrow exceptions. Build a “registration calendar” so your renewals don’t collide with grant deadlines.

For opportunities using SF-424 packages, follow the relevant application guide and the opportunity instructions. For example, HRSA provides an SF-424 application guide explaining electronic submission through Grants.gov and how to prepare application components.

Operational best practices for grant proposal submission:

- Submit at least 48–72 hours early when possible

- Validate PDFs, file names, and page limits

- Use a compliance checklist for every required attachment

- Keep a version-controlled “final packet” folder

- Capture confirmation numbers and submission receipts

Some funders explicitly warn about last-minute submissions and state that incomplete applications will not be reviewed, with exceptions only for specific system failures. A winning grant proposal process includes early submission as a risk-control measure, not a nice-to-have.

Strengthen E-E-A-T: Credibility Signals That Increase Award Odds

E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, Trustworthiness) isn’t just an SEO concept—it’s how reviewers decide whether you’re a safe investment. A winning grant proposal proves trust in concrete ways.

Experience: Show delivery history

Include:

- Past performance metrics (clients served, outcomes achieved)

- Similar projects delivered on time and within budget

- Case study snapshots (one paragraph each)

Expertise: Prove your team can execute

Add short bios focused on relevance:

- Program director credentials

- Finance and compliance capability

- Evaluation expertise (internal or external)

- Domain certifications (licensed staff, trainers, clinicians)

Authoritativeness: Anchor in recognized frameworks

Reference:

- Evidence-based models

- Standardized evaluation methods

- Regulatory frameworks when relevant (e.g., 2 CFR Part 200 for administrative/cost compliance)

Trustworthiness: Reduce perceived risk

Show:

- Internal controls and segregation of duties

- Data privacy and security policies

- Subrecipient monitoring approach

- Procurement standards and documentation plan

Real-world example: Two nonprofits propose similar programs. The one with audited financials, documented policies, a realistic dashboard, and a clear compliance plan writes the winning grant proposal—even if the other has a slightly more exciting idea.

Future-Proof Your Grant Proposal for 2026 and Beyond

Grantmaking is getting more data-driven, more standardized, and more compliance-aware. To future-proof your grant proposal, design it for faster review and stronger accountability.

Trends you should anticipate:

- Standardized applicant forms and structured data: NIH policy notices indicate movement toward “Common Forms” in core application components on specific timelines. Even if you’re not applying to NIH, it signals broader funder behavior: easier cross-application comparison.

- Stronger integrity and completeness enforcement: NIH emphasizes completeness and compliance at submission, and policy changes can become terms and conditions of award.

- More emphasis on security and training requirements: Research and data environments increasingly require security controls and training expectations, especially when handling sensitive data.

- Greater alignment between narrative and evidence: Funders increasingly prefer measurable outcomes, validated instruments, and realistic benchmarks.

Practical future-ready upgrades for any grant proposal:

- Add a one-page outcomes dashboard mockup (even if optional)

- Include data governance: who owns data, where it’s stored, retention, access controls

- Define performance management cadence (monthly, quarterly)

- Use “implementation readiness” proof: hiring plan, vendor quotes, partner MOUs

The future winning grant proposal will read like a deployable operating plan—clear outcomes, controlled risk, and auditable processes.

FAQs

Q.1: What is the most important part of a grant proposal?

Answer: The most important part of a grant proposal is alignment plus measurable outcomes. A beautiful story won’t beat a clearly aligned plan with credible targets, a realistic budget, and strong capacity proof. If reviewers can’t immediately see how your work advances the funder’s goals, you’re starting with a scoring penalty.

A practical rule: if your executive summary and outcomes section are strong, the rest of the grant proposal becomes easier to defend. Tie outcomes directly to activities and budget lines so nothing feels like filler. In reviewer terms, you’re building “line-of-sight” from need → approach → outputs → outcomes → budget.

Also, never ignore technical compliance. Funders may reject incomplete or late submissions without review, and some explicitly warn against last-minute submission issues.

Q.2: How long should a grant proposal take to write?

Answer: A competitive grant proposal often takes 2–6 weeks from planning to submission, depending on complexity. The writing itself might be only 30–40% of the work. The rest is assembling evidence, aligning partners, building a defensible budget, and validating compliance.

For government opportunities, add time for registrations and forms. SAM.gov registration and UEI assignment can be required for federal assistance applications. Regulations also discuss UEI/SAM requirements and limited exceptions.

If you’re under a tight deadline, prioritize a “minimum viable winning grant proposal”: crisp alignment, SMART outcomes, a feasible work plan, and a clean budget narrative.

Q.3: How do I write a grant proposal budget that reviewers trust?

Answer: Reviewers trust a grant proposal budget when it is:

- Derived from the work plan (not guessed)

- Within typical cost ranges for your region and sector

- Fully explained with calculations

- Consistent with allowable costs and procurement practices

For awards subject to Uniform Guidance, ensure your budget approach reflects administrative and cost principles under 2 CFR Part 200, which was substantially updated effective October 1, 2024. Even when a private funder isn’t bound by those rules, adopting that discipline increases credibility.

Q.4: What are the most common grant proposal mistakes?

Answer: The biggest grant proposal mistakes are predictable:

- Vague outcomes (“increase awareness”) without metrics

- Weak alignment to the funder’s stated goals

- Budget that doesn’t match the narrative

- Missing required attachments or signatures

- Waiting until the last minute to submit through portals and forms

Some funders explicitly list last-minute SF-424 submission as a common mistake and warn that late or incomplete applications won’t be reviewed. Treat submission as a deliverable with internal deadlines.

Q.5: How do I make my grant proposal stand out without exaggerating?

Answer: Use specificity instead of hype. A winning grant proposal stands out by:

- Naming exact outputs and outcomes

- Showing a credible implementation plan

- Including partner commitments and operational readiness

- Using clear evaluation methods and realistic targets

- Demonstrating governance, controls, and reporting discipline

Reviewers don’t need grand claims; they need confidence. If you can quantify outcomes, manage risk, and show proof of capacity, your grant proposal will stand out naturally.

Conclusion

A winning grant proposal is the intersection of persuasion and proof. It translates your mission into a measurable plan, a compliant budget, and an implementation approach that reduces risk for the funder. The best grant proposal writers build alignment early, design outcomes first, and use the narrative to make execution feel inevitable.

To win more often, treat your grant proposal like a product launch: define the need, position your solution, show capability, prove feasibility, and remove friction in submission mechanics. Stay current with registration and compliance requirements—especially for federal assistance where SAM.gov registration and UEI processes matter.